A VISION FOR

INDIGENOUS-LED RESTORATION OF OLD TOWN: RESTORING LOST MEADOWS, CANEBRAKES, SAVANNAS, & WOODLANDS

FRANKLIN, TENNESSEE

From:

introduction

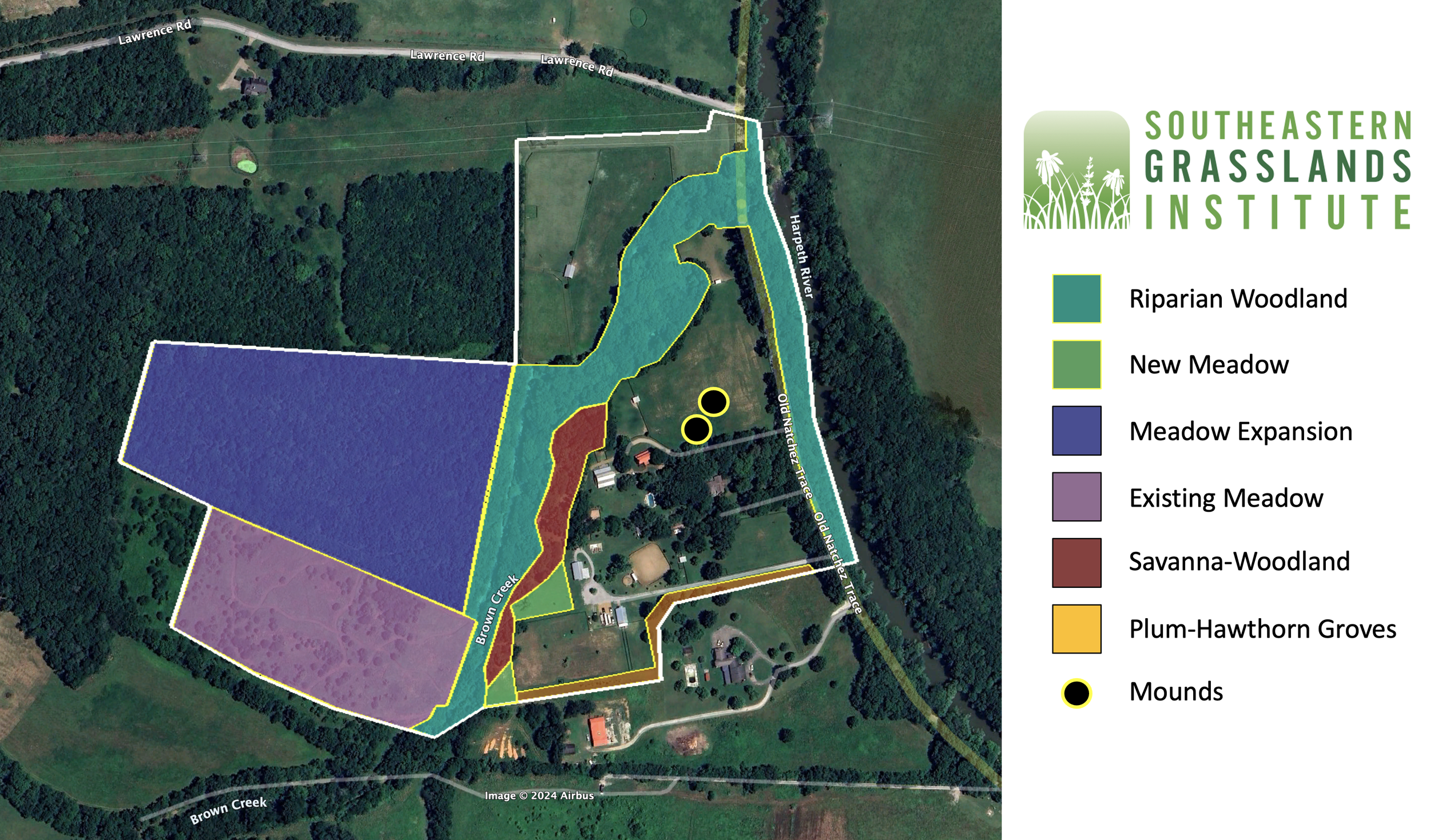

Old Town is a historical Mississippian-era Native American village along the Harpeth River in Williamson County, Tennessee northwest of modern-day Franklin near the northern terminus of the Natchez Trace. Records in the region show that indigenous peoples have lived in the Harpeth River Valley for more than 10,000 years. Old Town flourished between AD 1050 to ca. 1450, but was abandoned at least 230 years before the first French trappers visited the region in the late 1600s and 310 years before the first Anglo-American settlers arrived in the 1760s. Today, the 41-acre Old Town Farm embraces much of the historic town. Bill and Tracy Frist, present owners, have focused on conserving and preserving the cultural and natural history of Old Town. To complement the attention given to the cultural resources of Old Town, SGI proposes an indigenous-led effort to restore the natural resources of the farm, focusing on restoring and enhancing its wonderful meadows, wild plum thickets, savannas, and woodlands, and bringing back lost ecosystems such as canebrakes that were once abundant. Restoration of these natural ecosystems would not only help restore the cultural integrity of Old Town, but would also help to boost biodiversity and enhance the farm’s educational and outreach potential.

a prehistoric origin to old town’s meadows & savannas

Most people have been taught, falsely, that the Nashville region was a dense, vast forest prior to the arrival of Euro-American settlers and that the only reason why we have open landscapes today is because they were created by people through deforestation or burning. In reality, the region was home to a diverse mosaic of not only forests, but also open grassy woodlands and verdant oak savannas, punctuated by moist-to-wet meadows, dense canebrakes, and rocky glades. The Nashville Basin of central Tennessee was identified in a 2001 study by University of Tennessee ecologists as an "outstanding" hotspot of endemic biodiversity in eastern North America, due in large part to these grasslands (Estill & Cruz 2001). Many of these species are unique to Nashville Basin grasslands and their presence suggests an antiquity that requires at least tens of thousands of years off to evolve. Part of what makes the region special from a biodiversity perspective is the fact that these grasslands were always closely associated with woodlands, forests, and wetlands in a complicated and diverse mosaic. These landscapes are interrelated and many species depend on the ecotones shared between adjacent ecosystems.

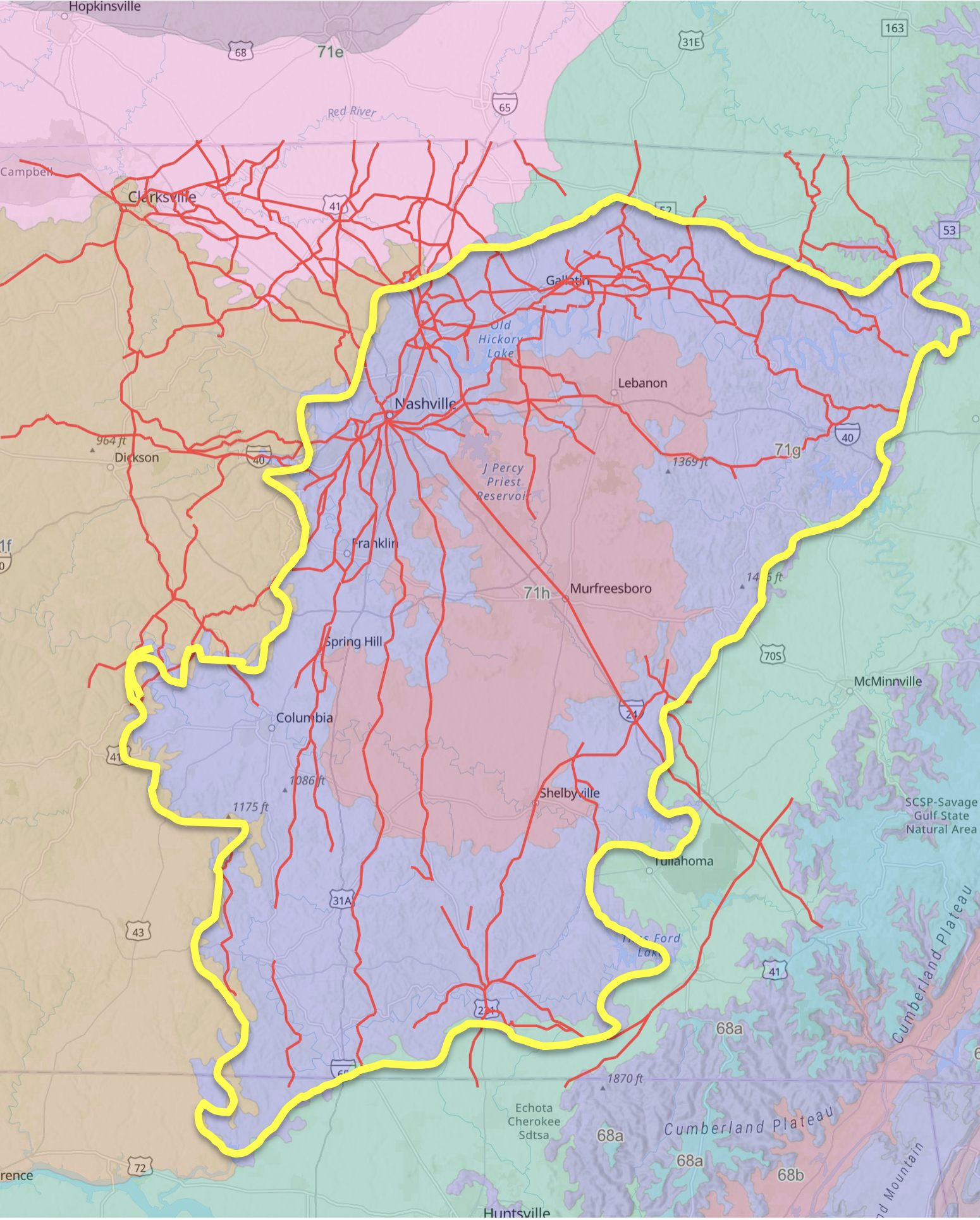

The map above by the Central Hardwoods Joint Venture shows the diversity of major ecosystems that would have been present in central Tennessee prior to European settlement as produced by landscape ecosystem modeling. According to the legend (upper left), a mosaic of ecosystems dominated the Harpeth River Valley. Forest (>80% canopy) and Oak Closed Woodland (50-80% canopy) occupied knobs and hills. Rolling low hills, terraces, and valleys were dominated by Oak Open Woodland (20-50% canopy), also known as Oak Savanna. Floodplain Forests (and associated woodlands) were found along major streams like the Harpeth River. Glade/Savanna Mosaic (<20% canopy) and Prairie/Savanna (<20% canopy) occupied large areas of the Nashville Basin Ecoregion. The inset map in upper right shows the 24-state Southeastern Grasslands Institute focal region with areas in green showing areas that included significant open, grassy ecosystems such as savannas, prairies, meadows, and open grassy woodlands.

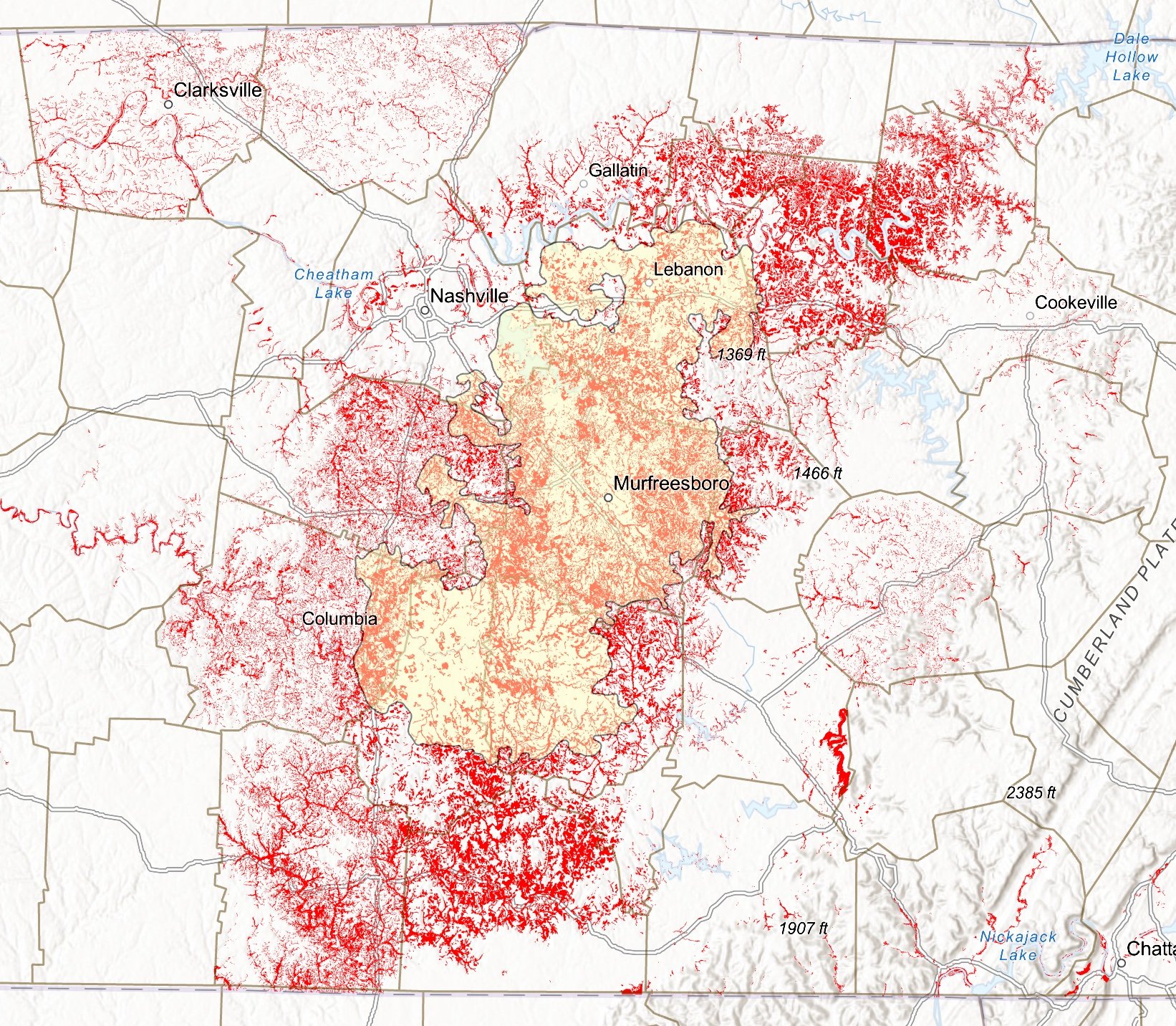

Map of central Tennessee showing distribution of Mollisol soils (grassland soils), in red, which are abundant in stream valleys and on stream terraces in the Nashville Basin Ecoregion.

The Nashville Basin has had an abundance naturally open ecosystems for at least tens of thousands of years, well before the first Native Americans arrived ca. 13,000 years before present (ybp). A suite of large mammals that required extensive grassy and open woodland ecosystems was present during the latter stages of the last Ice Age (Pleistocene). For example, fossils of two species of extinct horse found east of downtown Nashville along the Cumberland River, extinct mastodons found at Old Town and near CoolSprings Mall in Brentwood and tusks recovered from gravel bars of the Harpeth River (specimens at Tennessee State Museum), and extinct Giant Ground Sloths, all testify to the presence of open landscapes. These large animals needed open meadows, savannas, shrub thickets, and grassy woodlands for habitat and food sources. Certain tree species that are found today in the Nashville Basin such as Honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos) and Kentucky Coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus) have seeds which are thought to have been dispersed by these extinct large mammals. Extinct predators such as saber-tooth cats, the mascot of the Nashville Predators hockey team, Dire Wolves, and Short-faced Bears hunted the megafauna of the Nashville Basin, while smaller mammals such as Beavers engineered wetlands that helped maintain meadows and marshes, and Pocket Gophers burrowed into grassland soils of the region (Mollisols).

Native people have called Old Town and the Harpeth River Valley home for at least 500 generations, dating back to the last Ice Age. The fertile meadows and savannas that once occupied the Harpeth, Cumberland, Stones, and Duck River valleys and rolling landscapes of the Outer Nashville Basin attracted not only large game animals who came to water in the abundant streams and graze in the meadows, but they also attracted Paleoindians, Archaic, and Woodland-era cultures. These groups depended upon the rich variety of plants and animals that occur in the rich mosaic landscape that consisted of grasslands, woodlands, wetlands, and forests. The presence of these already open landscapes that fell under Native American management made these areas a natural choice for one of Earth’s few independent origins of plant domestication.

The abundant meadows would have made it easy to cultivate species like Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), Sumpweed (Iva annua), Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum), Erect Knotweed (Polygonum erectum), and Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album). The oldest record of common sunflower (Helianthus annuus) domestication, a species that today is considered native but weedy to the south-central U.S. in areas west of the Mississippi River, is from the Duck River Valley in central Tennessee where seeds have an estimated age of 5,081-4,640 BP (Crites 1987, Smith and Yarnell 2009, Miller 2014). They continued to supplement their diets with hunter/gathering and relied on nut-bearing Hickory trees and wild fruit trees such as Wild Plum. They may have traded some of these plants that were culturally important such as the Hortulan Plum (Prunus hortulana).

About 2,000-3,000 years ago, this shift to farming led to a cultural shift as tribes adopted more sedentary agriculture-based lifestyles that supported the growth of populous towns and villages in river valleys. These Mississippian "mound-builder" people occupied large villages up until the 1300-1400s in the valley of the Harpeth River at Old Town (Williamson Co.), Aaittafama (Davidson Co.), and Mound Bottom (Cheatham Co.), but they collapsed decades or a century before Columbus’s famed landing near Hispaniola.

After the Mississippian era, the lands of the Nashville Basin were the mutual hunting ground to multiple indigenous tribes. The Chickasaw and Choctaw came from the southwest, up the Natchez Trace. The Koasati, Yuchi, and Mvskoke came from the south and southeast. The Cherokee came from the Appalachians to the east. From the north and northeast came the Shawnee, Miami, Wyandotte, and Seneca. Finally, even the Illinois and perhaps other Midwestern tribes came from the northwest. It was a crossroads for many different tribes who came to the lush meadow and savanna lands abounding with wild game.

Based on the presence of an abundance of endemic species, the presence of extinct grassland-dependent megafauna, and the widespread abundance of grassland soils in the region’s valley lands, it is highly likely that Native Americans would have been attracted to the largely open, wildlife-rich Harpeth River Valley circa 13,000 years ago that abounded with open meadows, savannas, spacious woodlands, canebrakes, thickets, and forests. Native Americans likely would have used fire to maintain many areas in the Nashville Basin as open landscapes and this would have attracted large mammals such as bison, elk, and deer, species that had replaced the native horses, mastodons, American camel, and long-horned bison that disappeared just prior to the close of the Ice Age, about the time the first natives, the Paleoindians, arrived in the region.

Nick Fielder painting depicting Old Town, a Mississippian-era Native American village as it may have appeared ca. 1300.

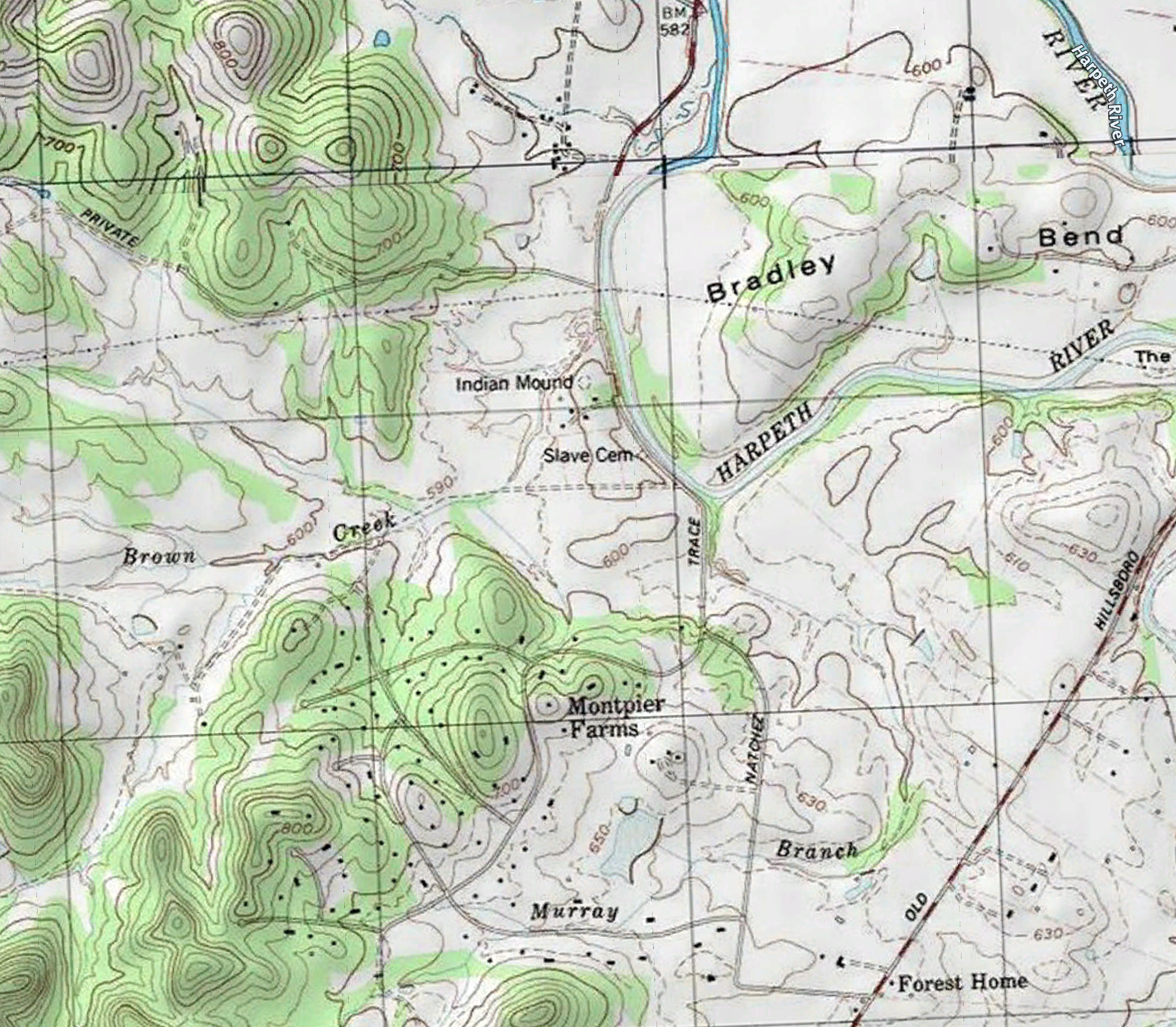

Old Town is indicated on this 1985 USGS Topographic Map by the location of “Indian Mound” near the confluence of Brown Creek and Harpeth River. Old Hillsboro Road, shown on the right of the map was historically the Great South Buffalo Road in the 1780-90s.

It is now clear that the first Euro-Americans attracted to Nashville were lured here by the presence of open meadows and savannas full of bison. Put another way, Nashville was largely settled and founded when it was in the 1760-80s because of grasslands! Some open meadows over limestone bedrock supported salt licks that attracted great herds of bison that would congregate to lick the salt-rich rocks and soil. French hunters and trappers, like Martin Chartier, Jean du Charleville, and Timothy Demonbreun, were the first to arrive, settling first at French's Lick, site of downtown Nashville, due in part to the large herds of bison and other game. The bison that congregated in this region ran vast networks of trails (bison traces) that extended like spokes of a wheel outward in all directions away from Nashville. These traces became the modern highways that today connect to neighboring towns like Franklin, Clarksville, Springfield, Columbia, and Murfreesboro. In the 1780s, what is now Hillsboro Road was known as the Great South Buffalo Road.

Painting depicting the historical bison meadows of the Nashville Basin that would have been similar to those found near Old Town in the mid-late 1700s. Painting by: Flávia F. Barreto for Artists & Biologists Unite for Nature (ABUN).

Map of historical bison trails mapped by historians from central Tennessee from the 1780s-90s.

This painting by local artist David Wright depicts the early longhunters who ventured into the Nashville area in the 1770s. It shows the mosaic landscape that would have existed with scattered forests as in the background and open meadows and savannas shown in the foreground. This is probably similar to what the meadows and buffalo traces would have looked like in Williamson County at the time of first settlement, especially along the buffalo trails that once ran where Hillsboro Road now does. The original vegetation composition of these meadows is not well known and only bits and pieces remain.

French traders who arrived from the 1680s-1760s were followed by the American longhunters of the 1760-70s (e.g. Michael Stoner, for whom the Stones River was named). These early settlers were drawn to the open meadows to hunt the abundant game. Eventually, settlement commenced, especially following the establishment of settlements by two of Tennessee's patriarchs, James Robertson and John Donelson, who arrived in 1779-1780. Evidently, much of the Nashville Basin was still open as meadows, savannas, open woodlands, and canebrakes by the time Revolutionary War veterans were awarded land grants in the late 1780s-90s. To this day, a number of communities in north-central Tennessee bear names that reflect their much more open grassy past, including Belle Meade (French for beautiful meadow) and Clover Bottom (Davidson Co.), Grassland and Fairview (Williamson Co.), Pleasant View (Cheatham Co.), Gladeview (Rutherford Co.), and Barren Plains (Robertson Co.). The photo collage below shows a few of Middle Tennessee’s remnant savannas that survived to the 21st century. Their beauty is astounding but these represent truly some of the rarest landscapes left in the South.

Oak savannas of the Nashville Basin have been depleted by >99.9% but a few remnants remain. They are windows to the past and were once used as grazing lands by early settlers, but they were also rich in wildflower diversity and thus were home to dozens of grassland birds and dozens of species of bees and butterflies. The large farms in the Nashville suburbs that were once home to these savannas could once again become very important in future conservation efforts. Such efforts could involve restoring combinations of native grasslands for forage and biodiversity.

degradation & loss of old town’s meadows & savannas

For at least 10,000 years, the lands of the Harpeth River Valley had been managed by the ancestors of the Chickasaw, Cherokee, Shawnee, Yuchi, and other tribes. Indigenous burning, in addition to bison and elk grazing, likely helped to maintain the open grasslands. But according to Middle Tennessee State University archeologist, Dr. Kevin Smith, who has spent decades researching the prehistoric Mississippian culture of central Tennessee, the use of fire by Native Americans in this region remains poorly known and unstudied archaeologically. In other regions of the South, such as the Little Tennessee River Valley in the Blue Ridge Mountains, there is a robust record of Native American fire that extends back thousands of years (Delcourt et al. 1986). By the end of the 18th century, the influence of these indigenous tribes on the native ecosystems of the Nashville Basin lessened as these tribes were forced to give up their hunting lands.

Following settlement by Anglo-Americans, in the 1780-90s, the grasslands and woodlands of the Nashville-region underwent rapid degradation. Soon after settlement commenced, elk and bison disappeared due to overhunting and these charismatic megafauna were gone by 1800. With the loss of bison and elk, and the onset of fire suppression, many meadow areas succeeded to canebrakes, thickets and forests. Other open meadows were converted to farm fields, such as croplands and pastures as they were the first places settled by Revolutionary War veterans awarded plots of land in the 1780-90s. With settlement, pigs, horses, cattle, sheep, and other livestock roamed the valleys and hills. Overgrazing is thought to have resulted in rapid degradation of the region's original grasslands. Overgrazing reached a zenith in the first few decades of the 1800s.

The highly fertile lands of the Nashville area were rapidly converted to fields of corn and cotton. In the 19th and 20th centuries, native meadows were displaced by non-native species such as bluegrass, orchard grass, timothy, red and white clover, and yellow and white sweet clovers. In the 1940s, "improvement" of pastures commenced as tall fescue was introduced on a wide scale. Very few natural grasslands survived these attempts at improvement.

The native grasslands that managed to survive into the 20th and 21st centuries are now largely confined to the rockiest sites where they have escaped the plow; these are limestone glades that are now isolated, tiny, rocky grasslands surrounded by thickets of redcedar and artificially dense “forests” of oak and hickory that should be open woodlands. While many limestone glades remain in the Nashville Basin, the same cannot be said of the original deep-soiled meadows and savannas. In fact, more than 99.99 percent of these have been eliminated. But, if we know what to look for, the signs of their former existence are still all around us.

At nearby Belle Meade Country Club, old massive bur oaks (Quercus macrocarpa) and chinkapin oaks (Q. muehlenbergii) tell a story with their broad spreading crowns. Their wide crowns and massive size are the result of having grown for centuries in relatively open conditions. Early in the lives of these trees, they would have existed as the dominant trees of the region’s open, grassy savannas, but later, after Anglo-American settlement, they continued to grow in open pastures as the native grasses beneath them were replaced by European grasses such as Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinacea), Orchard Grass (Dactylis glomerata), and Meadow Bluegrass (Poa pratensis).

This giant bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) at Belle Meade Country Club is estimated at 400 years old. This species primarily grows in savannas and when this tree first germinated it would have done so in an open oak savanna grazed by bison and elk.

MacGregor’s Wild Rye (Elymus macgregorii) is a savanna grass found in abundance at Old Town. This grass and its other wild rye relatives can provide nutritious forage for livestock. It grows abundantly under savanna-woodland at Old Town.

In areas too wet to cultivate, remnant meadows still can be found at Old Town and nearby areas. They are relicts of the former rich meadows and savannas that occurred in deep, rich, fertile soils. Examples include Tall Ironweed (Vernonia gigantea), Purpletop Grass (Tridens flavus), Nimblewill (Muhlenbergia schreberi), Eastern Gama Grass (Tripsacum dactyloides), Wild Senna (Senna marilandica), and McGregor’s Wild Rye (Elymus macgregorii). In some places, remnant wet meadow and marsh vegetation can be found in wet ditches, on creekbanks, or pond margins, such as in SGI’s 250 acres of restored wetlands in the Harpeth River headwaters near Eagleville in Rutherford County.

There is increasing awareness throughout the U.S. of the importance that private farms play for biodiversity conservation. In the eastern U.S., grassland birds such as meadowlarks and bobwhite quail are facing rapid population declines as the grassland habitat they need has steadily disappeared. Likewise, bees, butterflies, and other pollinating insects, are also experiencing major population collapses resulting from habitat loss.

Eastern Meadowlark was once common in the savannas of Middle Tennessee but now is deemed in a recent “Partners in Flight Report” as a “once common bird in steep decline.” This species is projected to be near functional extinction soon after mid-century.

Middle Tennessee is home to hundreds of species of pollinating insects but bees, like the American Bumblebee, and many butterflies, have disappeared due to loss of meadows, prairies, and savannas that were once full of native wildflowers.

In recent years, Nashville Metropolitan Davidson County has invested in the development of new large public parks, including Belle's Bend, the Warner Parks, Shelby Bottoms, Beaman Park, Lytle Bend Park, Mill Ridge Park, and Fort Negley. In June 2017, Radnor Lake State Park staff began restoring ten acres of meadow. The Tennessee Division of Natural Areas has been working to restore Couchville Glades and Barrens State Natural Area about 10 miles southeast of downtown Nashville. In spite of these very recent efforts to conserve grasslands on public lands, there have been few efforts to restore grasslands on Native American cultural sites such as Old Town. Nowhere is this more important than in the greater Nashville area, which is among one of the most rapidly developing regions of the South.

restoration of old town’s meadows & savannas

As the Nashville-Franklin area continues to see rampant development, it is more important than ever to ensure that sites like Old Town are preserved in perpetuity. Fortunately, the farm is preserved thanks to a conservation easement. Preservation is key for Old Town’s cultural assets, but restoration is essential for some elements that have been degraded or lost over time. For example, Bill & Tracy Frist are working to restore an original 1801 bridge that was damaged several decades ago. Meanwhile the natural assets of Old Town are in need of restoration, too.

Over the past two years, SGI staff have visited Old Town to document the farm’s biodiversity, advise on conservation matters, and conduct a prescribed burn. To complement the rich array of cultural history knowledge that exists for the farm, SGI proposes an indigenous-led plan to:

start working immediately to restore and manage Old Town’s canebrakes, meadows, savannas, and woodlands

draft a management plan to guide long-term restoration of Old Town’s native meadows, savannas, and woodlands

work with Old Town staff to develop educational signage and other outreach materials

conduct a baseline study of the natural history (ecology & biodiversity) of Old Town

our team

Thanks to three years of committed funding from USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Working Lands for Wildlife Program, SGI has been able to hire three full-time tribal liaisons, two of which are already in place and one is soon to be hired.

SGI’s tribal liaisons, Corlee Thomas-Hill and Gabrielle Patterson, will serve as joint project managers, working closely under the mentoring of Jeremy French (SGI Director of Restoration & Stewardship) and a soon-to-be-hired SGI Interior Plateau Restoration Ecologist. Gabrielle and Corlee will cultivate and develop an indigenous intern program and work with trained and trusted tribal volunteers to create an indigenous-led grassland conservation biodiversity & restoration team. Old Town will be their first pilot project of many yet to come across SGI’s 24 state focal region.

I. Indigenous-Led Restoration of Old Town

Old Town is such a culturally important site and has much known about it in terms of its cultural and archaeological history. But rarely are such sites managed in accordance with their historical ecology. SGI’s indigenous-led team will work with Old Town’s staff to design and plant new meadows and shrub groves, restore and manage existing meadows, and restore open savannas and woodlands. These efforts will not only help restore the ecological integrity of Old Town and enhance the educational potential of this important cultural site, but they will also restore important grassland and woodland biodiversity that has largely disappeared from the region.

1. Planting new meadows (0.6 ac)

At Old Town, the historic meadows have been degraded through more than 200 years of habitat loss, overgrazing, fire suppression, invasive species, and replacement of native meadows by non-native cool-season grasses and wildflowers. These meadows are dominated by typical lawn species such as Tall Fescue (Lolium arundinaceum), Meadow Bluegrass (Poa pratensis), Orchard Grass (Dactylis glomerata), and White Clover (Trifolium repens) — all species native to Europe. The once diverse open meadows have become sterile places for biodiversity.

There are two small open fields that will be restored to native meadow, collectively totaling 0.6 acres in size (one is 0.2 ac and the other is 0.4 ac). These non-native, species-poor lawn-like areas will be converted to diverse, healthy, vibrant, and species-rich native meadows. The degradation of these meadows took decades to complete so it should be no surprise that it will take a lot of effort to restore them. Restoration will require preparing the site for planting and seeding with a diverse native seed mix of locally to regionally-sourced seed.

Steps to plant the new meadows:

Plan for locations of trails and signage.

Prepare the site for planting by either using 2-5 rounds of broad-spectrum, aquatic-safe herbicide (due to proximity to Brown’s Creek) or covering the site with heavy-duty landscaping fabric to kill the existing weeds and non-native species.

Design a native meadow mix using locally- or regionally-appropriate species of native grasses, sedges, and forbs.

Plant one or two Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) saplings.

Purchase seeds from Roundstone Native Seed LLC and request seed harvested as close as possible to Old Town.

Use hand-seeder to broadcast-sow the seed mix, along with a cover crop of Browntop Millet. A cover crop will prevent soil erosion and provide a nurse crop to protect seedlings of native meadow species, but will not persist after meadow establishes.

Use carefully-timed bush hogging and prescribed burning to manage the meadow as needed.

2. planting a native shrub thicket-meadow border (0.9 ac)

Historically, native shrubs were abundant in the meadows and savannas of the Nashville Basin and no doubt at Old Town. They formed dense native thickets. Many of these species have beautiful flowers, are important for pollinators, and produce edible fleshy fruits that were important food sources for Native Americans and many species of animals. These native shrub thickets have largely been eliminated from the modern landscape in many places in an attempt to “clean up” farms and fields and in the name of “brush control.” The once vibrant native wild plum thickets at Old Town are deteriorating as they are overtaken by young, artificially dense forests of Hackberry, Elm, and Ash. They need to rescued soon by savanna-woodland restoration to bring in precious sunlight.

There is a long narrow corridor along one edge of the property (the southeast boundary) where we propose to plant a rather dense border of native shrub thicket groves and a narrow strip of meadow.

Steps to plant the new shrub thicket and meadow border:

Plan for locations of signage.

Remove existing non-native thickets of Bush Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense), Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora), and Winter Creeper (Euonymus fortunei) and treat them with herbicide to prevent their return.

Select native shrubs such as Cockspur Hawthorn (Crataegus crus-galli), Harbison’s Hawthorn (C. harbisonii), Frosted Hawthorn (C. pruinosa), Hillside Hawthorn (Crataegus collina), Sweet Crabapple (Malus coronaria), Rusty Blackhaw (Viburnum rufidulum), Glade Privet (Forestiera ligustrina), American Plum (Prunus americana), Chickasaw Plum (P. angustifolia), Mexican Plum (P. mexicana), and Hortulan Plum (P. hortulana).

Work with Landscape Architect, Tara Armistead, to design the shrub thicket planting with careful attention to species selection, sourcing native plant materials, spacing, and the relative balance between thicket and meadow.

Prepare the site for planting by either using 2-5 rounds of broad-spectrum, aquatic-safe herbicide (due to proximity to Brown’s Creek) or covering the site with heavy-duty landscaping fabric to kill the existing weeds and non-native species.

Design a native meadow mix using locally- or regionally-appropriate species of native grasses, sedges, and forbs.

Purchase seeds from Roundstone Native Seed LLC for the meadow mix.

Use hand-seeder to broadcast-sow the seed mix.

Use carefully-timed bush hogging to manage the meadow as needed.

Listen to Dr. Dwayne Estes (SGI, APSU) tell about the cool discovery of the Hortulan Plum (Prunus hortulana), found in 2021 at Old Town and its significance.

3. enhance existing meadow (8.4 ac)

There is a large existing meadow at Old Town that has become degraded over the past many decades. The Old Town meadow is out of balance due to the loss of bison and fire, leading to displacement of important native species by weedy Eurasian weeds. The meadow is at risk of becoming overgrown by early-successional tree species such as Hackberry, Black Cherry, and American Elm and non-native invasive species such as Sericea Lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), Bush Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), and Bradford Pear (Pyrus calleryana).

We propose to restore and enhance the meadow by using a combination of prescribed fire and strategic bushhoging, removing undesirable young tree species, using targeted herbicide treatments to control undesirable species, planting saplings of important woody species, and overseeding with additional meadow grasses, sedges, and forbs.

Leafy Prairie Clover (Dalea foliosa) recently grew in a small rocky grassland glade on Sneed Road. This species is a reminder of the past network of grasslands that once occurred in the region. Unfortunately the Sneed Road population disappeared about 15 years ago, but seeds have been preserved in a seedbank at the University of Kentucky that could be used for reintroductions at Old Town.

Enhancing the existing meadow will require:

Plan for locations of trails and signage.

Planting select species of native trees such as Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa), Chinquapin Oak (Q. muehlenbergii), and Kentucky Coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus).

Remove (cut, remove, treat stump with herbicide) most of the existing undesirable trees in the meadow including Southern Hackberry (Celtis laevigata), American Elm (Ulmus americana), Winged Elm (Ulmus alata), Green Ash (Fraxinus pensylvanica), Honeylocust (Gleditsia tricanthos), but leave one specimen or two of some of these species.

Encourage one or two specimen trees of other native trees such as Red Mulberry, Black Walnut, Persimmon because these are good savanna species.

Plant native shrub species such as Cockspur Hawthorn (Crataegus crus-galli), Harbison’s Hawthorn (C. harbisonii), Frosted Hawthorn (C. pruinosa), Hillside Hawthorn (Crataegus collina), Sweet Crabapple (Malus coronaria), Rusty Blackhaw (Viburnum rufidulum), Glade Privet (Forestiera ligustrina), American Plum (Prunus americana), Chickasaw Plum (P. angustifolia), Mexican Plum (P. mexicana), Hortulan Plum (P. hortulana), Southern Buckthorn (Sideroxylon lycioides), Roughleaf Dogwood (Cornus drummondii), and Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata).

Conduct a winter burn of half of the meadow each year, but always leave one-half unburned in any given season to serve as refugium for pollinators, invertebrates, box turtles, etc.

Bush-hog the meadow high (12”) in late February to prepare it for spring.

Overseed with native meadow species from Roundstone Native Seed.

Overseed with additional seeds of native species not available from Roundstone that must be collected from locally-sourced remnant meadows near Old Town.

Carefully mange invasive species such as Sericea Lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), Bradford Pear (Pyrus calleryana), Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora), and Nepalese Browntop (Microstegium vimineum) using herbicides.

Use aquatic-safe herbicide (due to proximity to Brown’s Creek) to spot-spray non-native cool season grasses such as Tall Fescue in fall and winter.

Introduce plugs or seeds of local rare species such as Leafy Prairie Clover (Dalea foliosa), a federally-endangered species, the federally-threatened Price’s Potato-Bean (Apios priceana), Indian Plantain (Arnoglossum plantagineum), Eastern Yampah (Perideridia americana), and the Duck River Bladderpod (Paysonia densipila).

Duck River Bladderpod (Paysonia densipila) is a rare spring mustard that is found only in river valleys in central Tennessee and north Alabama. It is now very rare in the Harpeth River Valley. We’d like to collect seeds of this imperiled species and establish populations at Old Town by overseeding into native meadows. They will flower and add color to the meadow in March-April.

4. restoring savanna-woodland (2-3 ac)

A 2-3 acre area behind the main house on the slope overlooking Brown’s Creek has a beautiful open tree canopy with dappled sunlight reaching the ground. This area would be beautiful to restore to a diverse open savanna-woodland. This would involve planting grass, sedge, and forb species. A trail system could be maintained to ensure this area stays accessible, open and pretty.

Restoring savanna-woodland will require:

Plan for locations of trails and signage.

Planting select specimens of native trees such as Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa), Chinquapin Oak (Q. muehlenbergii), and Kentucky Coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus) or others in the adjacent figure.

Work with an arborist to remove (cut, remove, treat stump with herbicide) any existing undesirable trees such as those that are diseased or dying.

Remove existing non-native thickets of Bush Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense), Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora), and Winter Creeper (Euonymus fortunei) and treat them with herbicide to prevent their return.

Select native shrubs to plant in the understory of the savanna-woodland, such as Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata), Blackhaw (Viburnum prunifolium), and Roughleaf Dogwood (Cornus drummondii).

Prepare the site for planting by either using 2-5 rounds of broad-spectrum, aquatic-safe herbicide (due to proximity to Brown’s Creek) or covering the site with heavy-duty landscaping fabric to kill the existing weeds and non-native species.

Design a native meadow mix using locally- or regionally-appropriate species of native grasses, sedges, and forbs.

Purchase seeds from Roundstone Native Seed LLC for a savanna-woodland mix.

Use hand-seeder to broadcast-sow the seed mix.

Manage with prescribed fire and periodic mowing.

5. reclaiming savanna lost to young forest (15 ac)

A block of young, early successional forest occurs on the southwest side of Brown’s Creek. Inspection of this patch of young woods indicates that it was formerly much more open meadow. It has all the clues of being a meadow in the not-to-distant past and can be restored in stages to savanna. We can understand that at first it might seem like a lot to “open up” this forest back to meadow or savanna. But doing so, would come nearer to restoring the conditions when it was a Native American village and would be more in line with the site’s historical ecology. The species of greatest conservation need in the young forest need fewer trees and open savanna-meadow conditions, and are at risk of disappearing with continued closure of the tree canopy. Given that meadow and savanna have disappeared by >99.9% from the region, this automatically creates a higher imperative to restore these imperiled ecosystems where they are ecologically appropriate, such as this site. Finally, we realize there are already about 8 acres of existing meadow adjacent to this young forest, but restoring more meadow and savanna will create a larger tract that can attract area-dependent species such as Northern Bobwhite Quail. For example, some grassland birds like Henslow’s Sparrow will not visit small-patch grasslands but need larger acreages before they will visit and use them.

Restoring savanna-woodland will require:

Important tree species for the Nashville Basin Savanna ecosystem to consider promoting at Old Town.

Plan trails and signage.

Mark trees and shrubs to keep.

Hire a contractor to thin the woods using a forestry mulcher (masticator) to open the site up substantially to a canopy coverage of 30-50%.

Ideally, desirable trees such as oaks, persimmon, black walnut, or red mulberry would be spared. See important tree species to preserve or plant in associated figure.

Keep healthy individuals or groves of Hortulan Plum (Prunus hortulana).

Follow-up mastication with control of invasive species and undesirable species using spot treatments of aquatic safe herbicide.

We would recommend some seeding with native species to combat the invasive pressure and speed-up recovery.

6. restoring riparian woodlands (10 ac)

Along Brown’s Creek and on the bluff of the Harpeth River are floodplain and riparian forests and closed-canopy woodlands dominated by oaks, hickories, and various hardwood trees and shrubs. Sadly, like most of the forests and woodlands of the Nashville region, non-native exotic species such as Amur Bush Honeysuckle, Chinese Privet, and Winter Creeper have invaded these woodlands and have permanently altered them. The result of this invasion is that the shrub and ground layer has been outcompeted by these invasives. The extra shade from the non-natives has led to a direct reduction in native woodland wildflowers, grasses, sedges, and ferns. These woodlands are in need of management to help control the invasive species. The ideal structure of these riparian woodlands should be as a semi-open Bur Oak-Shumard Oak-Shellbark Hickory Woodland that has lots of light reaching the floor in spring and is shaded during summer.

Restoring riparian woodlands & forests will require:

Aggressively treating non-native invasive species to remove and manage them. This would focus especially on Amur Bush Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), Japanese Honeysuckle (L. japonica), Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense), and Winter Creeper (Euonymus fortunei). These need to be treated with aquatic-safe herbicides.

Selectively remove other undesirable species to give more focus to desirable species such as nice specimens of Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa), Shellbark Hickory (Carya laciniosa), and Bitternut Hickory (C. cordiformis) and native shrub and small tree species.

Overseed woodlands with native woodland species to help combat the invasive species pressure and speed-up recovery. Key species to include include Virginia Bluebells (Mertensia virginica), Woodland Brome (Bromus pubescens), American Beak Grass (Diarrhena americana), and Atlantic Camas (Camassia scilloides).

Purchase seeds from Roundstone Native Seed LLC for woodland mix and supplement with locally-collected seed sources.

7. canebrake restoration

River Cane (Arundinaria gigantea) is one of the most culturally significant plants at Old Town. This species was also very important to the Native Americans who lived here for thousands of years. Cane was used for many different aspects. There are a few places at Old Town that would be ideal to restore the canebrake ecosystem. These could be restored along the edges of the existing meadow or planned meadows or in places under riparian woodlands or savanna along Brown’s Creek.

Restoring canebrakes will require:

Propagate native cane from rhizomes and grow them out as plugs to plant, forming new canebrakes.

Plant select herbaceous species, sedges, or native grasses in and around the canebrake such as Cherokee Sedge (Carex cherokeensis), Bindweed (Calystegia fraterniflorus), and MacGregor’s Wild Rye (Elymus macgregorii).

II. Prepare a Management Plan

SGI staff can prepare a written plan that will provide a roadmap for future stewardship. There are clearly some restoration activities we can do now without a plan that are evident. We know for example that prescribed fire, well-timed mowing, invasive treatment, removal of undesirable species, and increasing desirable species and habitats are all things that can be done as soon as time and budgets allow. These need action as much as anything. However, longer range planning is important to strategize about how to fund, maintain, and guide restoration activities over short, medium, and long-term time scales. Such planning will help ensure the longevity of restoration activities and those are things SGI can assist with when it comes to planning for the needs of Old Town’s meadows, savannas, and open woodlands, each of which will require management to persist, as they did for hundreds of generations since the Ice Age.

III. Education & Outreach

SGI staff will help Old Town staff develop educational and outreach materials related to Old Town’s historical ecology and ecosystems. This can take the form of helping to design signs, kiosks, website materials, ArcGIS story maps, documentary videos, social media pieces, etc. We can also be available to assist with educational tours for visitors.

IV. Document the Biodiversity of Old Town

Our staff will work with Old Town farm staff and SGI’s network of volunteers to create and maintain an iNaturalist project. They will follow SGI’s 9-module online guide to set up and maintain the project. This project will be used to track all biodiversity data and maintain species lists for plants, animals, and fungi at Old Town.

V. Research pre-settlement & early settlement ecological history of Old Town

SGI will continue searching through archival records, old maps, interviewing elders, searching tribal records, and collaborating with archaeologists who have studied Old Town’s history and prehistory to help better understand the original landscape on and around Old Town. SGI already has a good start on researching the history of the Nashville area on which we can build. These data would contribute to SGI’s new $2 million funded project we call Grasslandia, which is an online web portal that will host interactive maps showing historical and modern grasslands, biodiversity data, and cultural history data related to historical grasslands.

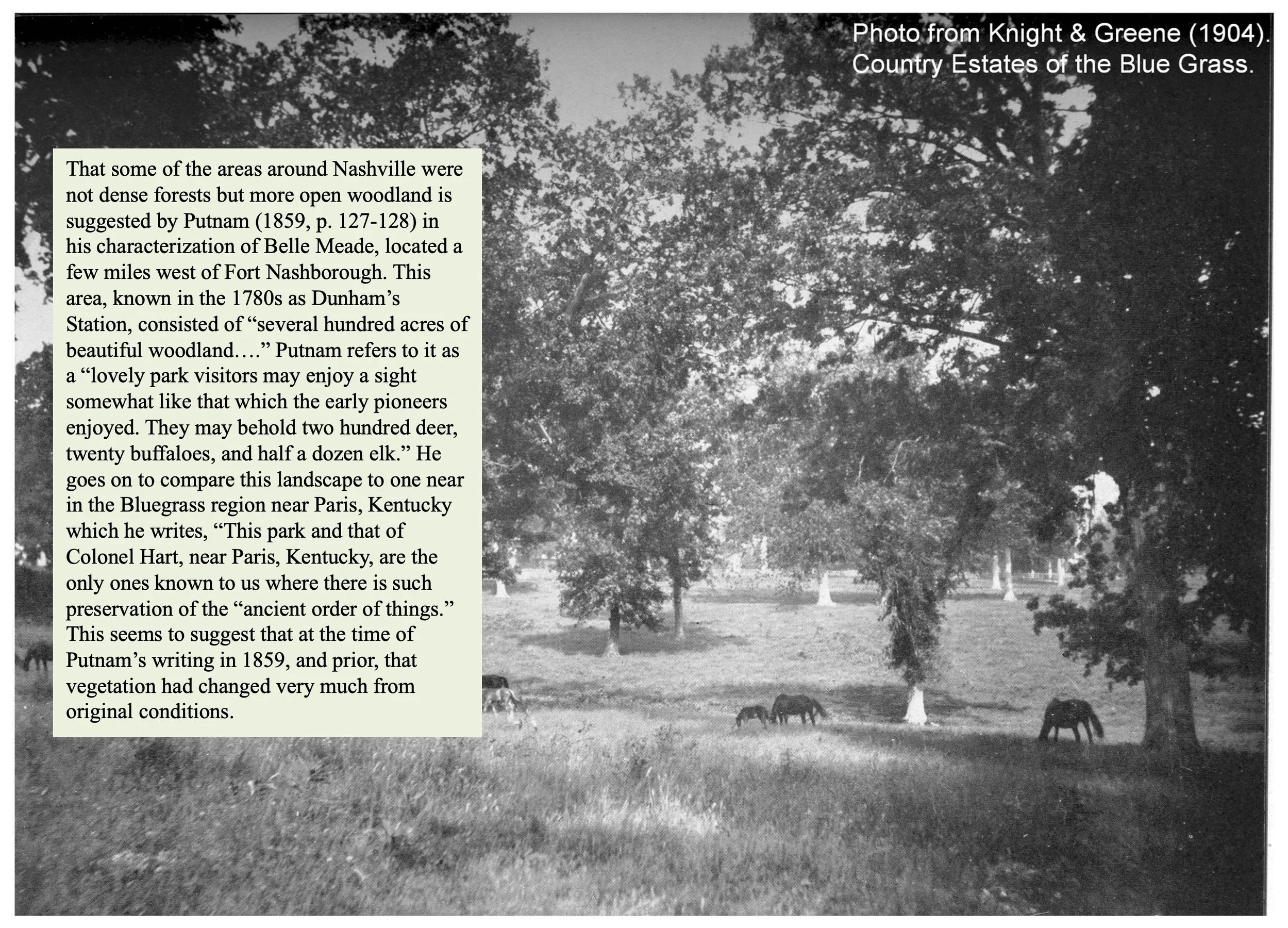

Photograph from 1904 from the Kentucky Bluegrass. These photos show what much of the Bluegrass and Nashville Basin savanna-woodlands would have likely looked like in early settlement times.

VI. Timeline

To be determined. We are prepared to get started this summer and can arrange an in-person meeting as soon as everyone is ready.

VII. Budget

To be determined. We’ve presented a menu of items to choose from according to your priorities. Currently SGI’s key positions to support this project are funded, including our 3 tribal liaisons (2 hired, 1 more on the way) and our Director of Stewardship position. The main costs would be the actual restoration, management, or planting costs and we could use additional travel funding for this project to cover Corlee and Gabrielle’s travel as needed to manage the project. Corlee is based in Cherokee, NC and Gabrielle is based near Shreveport, Louisiana.

VIII. References

DELCOURT, P.A., H.R. DELCOURT, P.A. CRIDLEBAUGH, and J. CHAPMAN. 1986. Holocene ethnobotanical and paleoecological record of human impact on vegetation in the Little Tennessee River Valley, Tennessee. Quat. Res. 25:330-349.

more to be added…